You can disagree with him all you’d like on immigration reform, but Florida Senator Marco Rubio is correct in saying that this easing of sanctions, and normalizing relations with the murderous Castro regime in Cuba will not end the human rights atrocities that have been going on in that country since the Fidel Castro first took over.

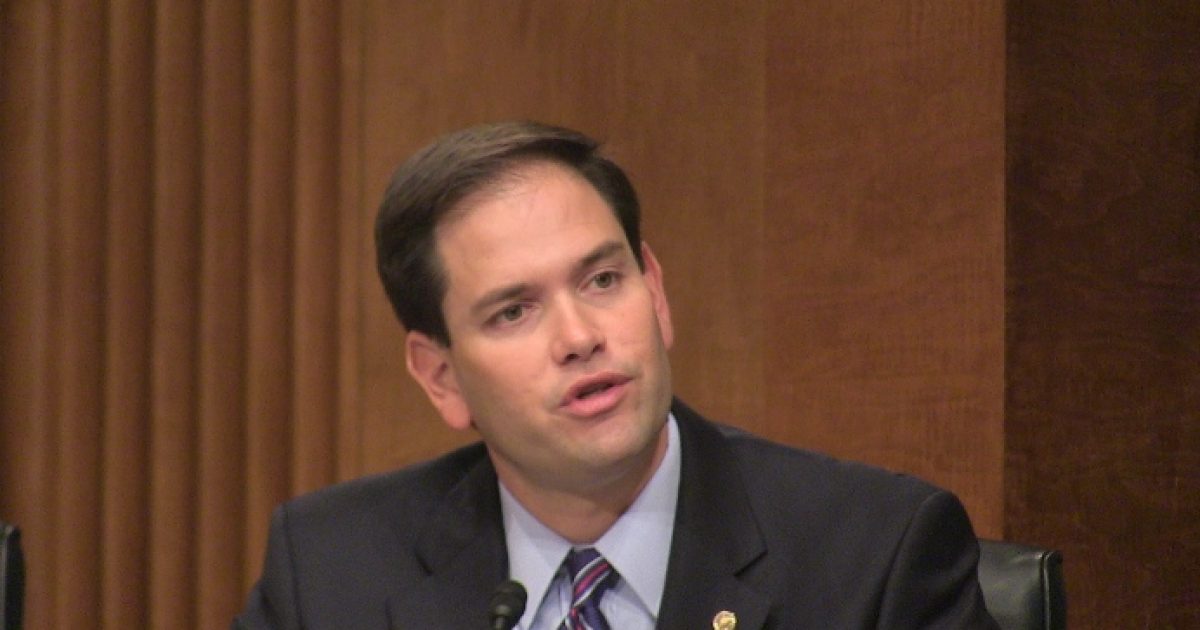

After taking the gavel at his new post as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Transnational Crime, Civilian Security, Democracy, Human Rights and Global Women’s Issues, Rubio took the State Department to task on the Obama administrations push to make nice with the Castro brothers in Cuba.The Miami Herald offered this:

In the first of several congressional hearings on President Barack Obama’s policy, Rubio laid into the administration. Rubio reiterated his strong objections, saying he had “deep reservations” about — and “direct opposition” to — many of the changes being proposed.

Do you think the 2nd Amendment will be destroyed by the Biden Administration?(2)

He did so, he said, “for the simple reason that I believe that they will not be effective” in bringing about meaningful change to Cuba.

The West Miami Republican and potential presidential candidate has emerged as Congress’ chief critic of the new Cuba policy. In a Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee hearing, Rubio said the opening to Cuba neglected the reality of human rights abuses on the island.

Rubio, whose parents came from Cuba in 1956, took the reins of the Western Hemisphere subcommittee as Republicans took control of the Senate last month.But other senators were supportive of the new Cuba policy, including Sens. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat from California, and Jeff Flake, a Republican from Arizona. Flake said it was time to relax travel restrictions between the United States and Cuba, something he has pushed for years.

The administration, represented by Roberta S. Jacobson, the assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, contended during the hearing that the United States was pursuing the opening with its eyes wide open, and that it was time to pursue a different strategy from the one that has failed for a half-century.

“This administration is under no illusions about the continued barriers to internationally recognized freedoms that remain for the Cuban people, nor are we under illusions about the nature of the Cuban government,” said Jacobson, who led the U.S. delegation in last month’s talks in Havana. “When we sat down with our counterparts in Havana, we were clear that our governments have both shared interests and sharp differences.”

Ticking off a list of issues over which the two countries are negotiating, Jacobson said she raised with Cuban officials “our concerns about its harassment, use of violence and arbitrary detention of Cuban citizens peacefully expressing their views.”

Rubio and New Jersey Sen. Robert Menendez, a Democrat, are key Senate opponents to the policy.In his opening statement, Menendez said that despite the length of the negotiations between U.S. and Cuban officials, the two sides hadn’t come up with anything worthwhile.

“Let me be as clear on this issue as I have been since December,” he said. “Eighteen months of secret negotiations produced a bad deal — bad for the Cuban people. While it may have been done with the best of intentions, in my view, we’ve compromised bedrock principles for minimal concessions.”

He continued: “At the end of the day, 53 political prisoners were released while so many more remain in jail and the Cuban people — those who suffered most under the regime — still have zero guarantees for any basic freedoms.”

The Obama administration’s plans to open the door to Cuba became public with a dramatic unveiling in December, with the release of USAID subcontractor Alan Gross and the announcement that trade and travel restrictions will be eased and that the United States would work to reestablish diplomatic ties with Cuba.

In his questioning, Rubio drilled into the fact that Jacobson’s office was not the prime mover on the new Cuba policy. And he wanted to know which pro-democracy groups in Cuba were consulted.

He also pushed for a declaration from the administration that the opening of any diplomatic presence, such as a U.S. embassy, wouldn’t come with restrictions on the ability of embassy personnel to visit democracy activists. Citing recent public comments from a top Cuban official, Josefina Vidal, Rubio asked Jacobson whether the United States would ever go forward with an agreement that — as Vidal indicated — made certain pro-democracy activists in the country off-limits to embassy personnel.

The United States also limits the travels of Cuban diplomats in the United States.

Vidal actually said during a Cuban Television interview earlier this week that Cuba was willing to have a discussion about freedom of movement for embassy personnel but that it was important that the behavior of U.S. diplomats in Havana change.

She accused them of training, supplying and financing “elements within our country who act against the interests of the state, the government and the Cuban people.”

In a back-and-forth with Jacobson, Rubio pressed her for an answer.

Rubio: “Can you say … that under no circumstances will the United States ever agree to limit the ability of our personnel to interact with democracy activists … as a condition of expanding our embassy operation?”“I don’t know if that is a real condition on their part,” said Jacobson, indicating that Vidal’s remarks may have been more for domestic consumption in Cuba than the Cuban negotiating position.

But Jacobson said the United States wanted to have the “greatest possible ability” to interact with people on the island.

Rubio: So we will never agree to limit our personnel?

Jacobson: “We’re going to keep pushing to get those restrictions lifted as part of getting an embassy…”

Rubio cut her off, saying, “Secretary Jacobson, this is a pretty straightforward question.” Asked the question again, Jacobson said that she “can’t imagine that we would go to the next stage of our diplomatic relationship with an agreement not to see democracy activists, no.”

The hearing also included testimony from Cuban human rights activists, including Berta Soler, president of the Ladies in White, a Cuban dissident organization. Speaking through translators, the activists described the repressive life on the island.Rubio dominated the hearing, though Flake and others made it clear that Rubio’s stance faces resistance in Congress. But Rubio and his Republican allies could crack jokes about their differences.

At one point, after a long reply in Spanish from Soler, Rubio began talking before the translator had performed her role.

Rubio apologized, saying that he had understood Soler and forgot that his colleagues in the Senate often couldn’t.

“What I’ve told Sen. Flake is don’t worry about the translation,” Rubio joked. “I’ll let them know later what they’re saying.”